Carl Phillips is the author of numerous books of poetry, including Silverchest (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), Double Shadow (2012), Quiver of Arrows: Selected Poems 1986-2006 (2007) and Riding Westward (2006). His collection The Rest of Love (2004) won the Theodore Roethke Memorial Foundation Poetry Prize and the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Male Poetry, and was a finalist for the National Book Award.

[A. Van Jordan’s bio here.]

A. Van Jordan: I’m curious about your use of Greek and Latin in your poems, not as symbolism or mythology, but as an influence on the subtext and syntax of your poems. Well, I’m making assumptions now. I guess I should first ask if it influenced your work and, if so, in what ways?

Carl Phillips: It took me a while to be convinced that studying classical languages had an influence on how my sentences work in poems, but I can see that the inflected nature of Greek and Latin—in particular, the way in which a sentence doesn’t really settle into clarity until the very end—must have influenced me. But before studying classics, I took German for five years when I was a kid, so it may well have started there. My sentences are pretty reflective of the way I’ve always thought, as far as I can remember. I think it might more likely be the case that my way of thinking drew me to inflected languages…The other, more obvious influence of the classics, for me, was in discovering the Greek lyric poets and seeing both the nakedness of the emotion, and the way in which that emotion could be so economically conveyed. I was also fascinated with the way the Greek tragedies wrestle with how vexing it can be to be human—that’s certainly been one of my subjects from the start.

Jordan: You’re a good reader of your poems, too. I’m wondering if you read your poems aloud as you write and edit. Are you conscious of the nuances of influence on an aural level? That is, what would you say is an aural influence on the work? Music? Other languages? Colloquial speech?

Phillips: I do read the poems aloud, yes—not while writing, as much, but in the revision stage. I want to test for where things are too rough, or aren’t rough enough, where they fall into patterns of sound and whether or not those are meaningful or distracting patterns. I want the sentences, however roundabout they may seem at times, to deliver clarity—people have spoken of the work as difficult, but the sentences themselves are generally clear, they just aren’t perhaps in the English that people immediately expect, or are used to reading these days. My road-test for a poem is when I read it, finally, to my partner, who isn’t trained in any way as a poet or reader of literature. He’s a photographer, and thinks in an entirely different way. If a poem makes sense to him, I think it should do so for any patient reader of poetry….I guess I strayed from your question about aural influences. I can’t think of any, to be honest. I listen to a huge amount of music, but I don’t think I can say it’s influenced the poems. I would just say that music has an influence, somehow, in that I sometimes have the sense of wanting to write a poem that captures in words what a particular passage of music captures without words.

Jordan: When I look at the sequencing of poems in your books, it’s clear that the poems fit together over the course of a section and—again, in other ways—over the course of a book. The sections have an arc that feels like character development for an emotion. Does that make sense? I get a sense of an emotional arc taking place and then a movement to other nuances of that emotion in another section. And, by the end of the book, a full experience of this emotion. And when I say emotion, I don’t simply mean something like sadness or joy. I mean longing, vulnerability, exploration, experimentation, etc. I guess I see actions that carry emotions. Are you conscious of this sort of thing?

Phillips: I love that description—“character development for an emotion.” That’s exactly what I hope is the result when the poems are finally brought together as a book. I’m not conscious of anything like that while writing—I can’t decide, for example, what a book’s subject is, and then write about it. I just write individual poems, and eventually there’s this feeling that a certain ‘project’ has shut itself down. That’s when I go through, and try to see, of say 45 poems, whether there are 30 or so that seem absolutely good enough to be in a book (there are always poems that are just doing the same work, so a choice has to be made). And once I’ve narrowed the poems down, I start trying to figure out how they’re working together, or what kind of work can happen in various configurations. It’s both a frustrating and weirdly magical process, I find—and it’s been different for every book. By the end, though, I do have a sense of the emotional and/or psychological elements at work, and a clear sense for myself of a trajectory. I don’t mean anything like a conventionally narrative trajectory, but the multidirectional kind of trajectory that attaches to psychological and emotional life.

Jordan: Is the process of putting together a book of selected poems different than a single collection? That is, has it been a different experience working on Quiver of Arrows than your other collections?

Phillips: I found it very difficult. In the end, I wanted to have a book that gave a sense of the development of a sensibility, and of the concomitant development of a poetic line that might enact that sensibility. What surprised me is that it didn’t mean necessarily picking all of my favorite poems or of poems that have been especially popular with readers. Instead, I had to really look at the degree to which each poem was pushing something forward…I had to let go of the idea of selecting poems from each book that would give a sense of the trajectory of that particular book—instead, I wanted to imagine there wasn’t any individual book, and that this was about a longer sense of apprenticeship, which, in the end, it has been and is.

Jordan: A question I ask my students at the beginning of every semester is “What does poetry do?” That is, with new media, graphic novels, hyper text, and other genres that I know very little about, what does poetry offer that other genres don’t? What’s the utility of poetry today?

Phillips: One of the things that poetry does—or can do—is slow us down; it invites us to spend time looking at something and considering it; which is to say, it reminds us of the possibilities for being alive in the world, and it helps us to see the world anew and more keenly. Obviously, this can happen with a novel, as well—but the particular distillation that poetry tends toward provides its own lens. Likewise, we learn what it means to be alive and we see the world when we read a newspaper, but that seems to me to be mere information. Poetry gives us something of the texture. It’s like the difference between the body and a picture of the body.

Jordan: Do you feel any burden to speak to a specific audience? Maybe burden is not the right word in this case. Based on my family background, I often want to connect with people who are not poets and people who are not even college educated. I like it when non-traditional poetry audiences—public libraries in urban areas, prisons, homeless shelters, government work sites, etc.—connect with the poems. Over time, I realized this is important to me because these audiences represent my family and the community in which I grew up. What about you? Does anything like this play in the back of your mind as you write?

Phillips: I certainly want my poems to connect to audiences that aren’t all poets, yes. I grew up on air force bases, neither of my parents had gone to college, both grew up poor. I went to public schools and even later, when I went to Harvard, my job was cleaning toilets in the dormitories. I mention all this to say that I connect to where I came from much more than to the academic and decidedly privileged world where I write and teach now. This doesn’t make me write any differently—but what I notice is that it’s not fair to assume that you have to write in a more ‘accessible’ way, if you want to reach non-academic audiences. All you need to do is write honestly—write the poems that you have to write, for yourself—and then you need an audience of people who want to hear poetry. I’m amazed at how certain poems of mine, which have baffled some reviewers of poetry, are apparently quite clear to a high school class, or to people who have come to a public library event. I did some work with the National Book Foundation for a week, years ago, where I went into the Bronx and read and spoke about poetry to women in a battered women’s shelter one day, on another day to ex-convicts who were studying for their GED … They wanted to hear poems, they wanted to talk about the struggles of being alive, and the joys of being alive—things that every human being experiences, not just those who are in writing programs, for example. So yes, that matters a great deal to me.

Jordan: Yes! It shows. In The Rest of Love, I get a sense of your dialogue with the world. The tension of love and unrequited love is present, but the layers of tension are plentiful: call and response, possession and loss, control and lack of control. In the end, you close with “Crew”; when the boys call back, it feels transcendent of all the tensions that come before it. I don’t want to go down the road of your authorial intentions, but I do wonder if you are conscious of the layers of tension in your books? It might come during revision or during the sequencing of a book or in individual poems. If it comes, at what stage(s)?

Phillips: Hmm. Very tough question. I don’t think I am especially aware of the different layers until I start trying to sort out how a group of poems might work together as a book. Within individual poems, I write—insofar as this is possible—pretty much free of self-consciousness, or of consciousness of writing a poem about a particular thing. I just want to get everything down, and it’s often not for many days after I’ve finished a poem that I have a firm sense of what is at stake in that poem. Sometimes, I know it’s finished, but I don’t know exactly what it’s ‘about,’ yet…Anyway, when I start putting a manuscript together, that’s when I get a sense of what the significant resonances (emotional, psychological, not so much straightforward narrative) are, and I start to try to gauge what various arrangements of the poems could generate in terms of sequence of movements. This all sounds pretty odd, I think, but it’s maybe a bit like trying to put together a symphony, where you want to have some quieter areas, some louder ones, some that might be all horns, etc. Except that it’s a kind of symphony of the psyche…When those boys ask their question about the soul at the end of “Crew,” I suppose it’s a form of transcending—I think what they’re transcending is the earlier-held belief that something like a soul could in some way be understood. By the end, they are either giving up, or maybe giving in, to their restlessness; by giving in to the vulnerability of the interrogative, they transcend the illusion of stability that the declarative equals.

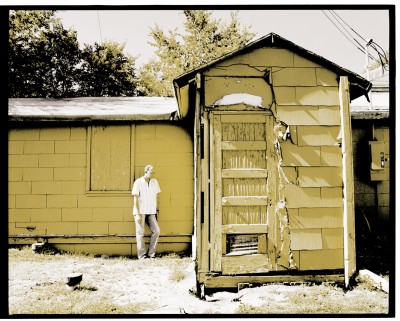

Jordan: Would you say you have a proclivity toward nostalgia? I say this not in some old fashioned kind of way, not in the return-to-the-good-old-days kind of way, but I’m curious about your curiosities. I remember once watching your face in that locked-in-days-gone-by hardware store in Black Mountain; it was a look I hadn’t seen on you before, but it was a look that explained your eclectic iconographies that come up in your poems. One other time I was surprised to see you with a lariat—I think that’s what it’s called, at least—you found somewhere else in North Carolina or Vermont, maybe. I thought, I wouldn’t expect to see him with one of those; I had just bought Coin of the Realm, and then I looked up about a year or two later, and there was Riding Westward. So, I guess I’m asking what’s up with that? What sort of things are you curious about and are they connected, in some way, to nostalgia of some kind?

Phillips: I’m going to have to be on my guard next time we head to a hardware store! Well, I think I have an interest in things that people might think of as nostalgia, though for me they’re very much part of the contemporary world. And I think these interests then come across as eclectic, because there’s this idea that certain things have fallen into the realm of nostalgia. A lemon-juicer, for example, from the 1930s or so, when they used to be made of heavy glass—this seems much more efficient than some of the new contraptions that are made. Or more to the point, I see no reason to replace the device I use, if it’s still working, with something more modern … Someone recently thought it was quaint, maybe old-fashioned, that I cook everything from scratch—I’ve had dinner guests who I suspect think I’m trying to show off, in fact. But I like the taste of homemade bread better than store-bought—if it’s nostalgia, it’s nostalgia for how things used to taste, which is the reason to grow your own tomatoes, as well … It’s true that I have one odd thing I like to acquire, horse-tack, things like bridles and crops and saddles. But while it’s true that I’m no cowboy, cowboys do still exist in the world and actually use these things, so that makes them contemporary. It depends on where you’re literally coming from. Friends on the east coast find the fields of Missouri strange and old-fashioned. I’ve been asked, because of the deer and foxes and other animals in some of my poems, where I imagine them taking place, as if there were no place left where wildlife lived. These are animals I see in my backyard in Massachusetts, where there’s a lot of conservation land; just this afternoon, in the heart of St. Louis, I watched a raven viciously attacking a hawk in flight—I pulled the car over to watch until they disappeared from view. Nostalgia? Eclectic?

Jordan: That sounds like a scene from a movie. The film critic Andrew Sarris once said that we Americans get so excited about mediocrity because there’s so much bad art these days. A movie comes out that seems like it has potential to be good, and we praise it as the greatest film in years. He felt—at the time, at least—that opera, film, music and literature in general was in trouble. Well, this was ten years ago in a film class at NYU. What do you think about this with regard to poetry or music or film or any art? Are we in trouble or are things just fine? Have you noticed any trends in any area of art, per se?

Phillips: I think there’s always been a preponderance of what I’d call the mediocre, because what’s mediocre is what tends to appeal to the broadest range of tastes, and it seems to be human to want to be liked by as many people as possible. It also tends to be human to want to be rewarded by as many people as possible—that’s a reason to make a mediocre movie; it often brings in much more revenue than a more sophisticated, intelligent movie. But I don’t get alarmed, because what happens over time is that the mediocre falls away and what’s memorable gets remembered. We think of certain ages of great poetry, but there was a lot of mediocre stuff that was no doubt also getting written in those ages; with time, that work has faded from view. I think what’s important is to make the poems—or any other kind of art—that you have no choice but to make, the work that is authentically from yourself. With luck, it might resonate with other readers (sticking to poetry), but it might not, and that could have to do with many things, including that the work is original, that people have a resistance to the new and original, and that the trends can sometimes not be able to accommodate something different. But it all seems to come around. We’ve been in the age of the fragment, it seems, for quite some time—and yet I heard a young poet at a reading recently say that she had begun to miss sentences, and had made a conscious point to use longer, more periodic sentences in her poems. But even as I speak of the age of the fragment, that varies, too. Sometimes it’s the case that a certain poetry is getting more attention, but that doesn’t mean that other types aren’t being written somewhere. It would sometimes appear that there’s a trend to the more demotic poem, where if there’s difficulty to be found at all, it’s not going to happen at the level of language; but I think it only appears to be a trend because that’s what we see appearing in journals and often winning awards. That doesn’t mean that poets aren’t out there writing poems that challenge the possibilities for how language can be deployed. Nor, by the way, does it mean that the latter are better or worse than the former, it just means that there is a huge range of art being made. We make what we make. And we appreciate what we can. And taste is constantly shifting, even within the individual.

Jordan: The shifting of taste within the “individual” seems to touch upon identity. In your essay “Boon or Burden” you point out how “the self seems increasingly to be understood as a construction of many identities, even as race becomes more and more impossible to pin down.” And earlier in that same essay you note that “the challenge then becomes one of determining how the poem can resonate both at and beyond the level of identity.” What are the levels of identity in your work and where do you hope it resonates beyond? I think it’s safe to say that we—not just African American men, but we poets in general—don’t want to be marginalized in some way by our cultural, sexual orientation, gender or regional identities. So I’m really asking how far—on a level of identity—do you see your reach and what are the many frequencies of it?

Phillips: Well, I think it’s changed over the years. I certainly had poems in my first book where the people were identifiably African American, or where the issue was clearly that of race. And in that book and the second one, I was very much wrestling with ideas about sexuality, and about the homoerotic in general—I’d just come out as a gay man, so that makes sense, to me. But I tend to write around and toward subjects that I find difficult to reconcile in my mind. That’s how I found myself moving to such subjects as sexual restlessness and how to put that next to ideas of fidelity, for example; or I’m forever interested in the way in which morality seems to be flexible at best, slippery at worst, and yet society seems so concerned with putting morality into some kind of straitjacket. So I like to think my poems reach toward what it is to be human, susceptible to the senses, but also in possession of consciousness and self-awareness, which means we can feel things like guilt or we can know what it is to not feel guilty (speak of a boon and a burden!).

It’s not that I have ‘solved’ the conundrums of race and sexual identity, by any means. But I don’t happen to wrestle with those specific issues in my daily life—I feel that I know exactly who and what I am; I’m not struggling with the ‘shame of being gay,’ for example, but that’s in part because I’ve had no difficulty being accepted as gay. I’ve certainly experienced racism, lots of it, in the course of my life, but it hasn’t shaken my sense of pride in being who I am. But I also know I’ve just been lucky in much of this.

Jordan: A sense of pride in being who you are is multifaceted, though. Your work has many frequencies, and there’s been a lot of movement in your work over the years, a real trajectory on many different levels. One of the more pronounced trajectories has been your treatment of spirituality—I’m using this word in lieu of something better, I certainly don’t want to say religion or faith, for instance—over time. When I look at In the Blood and see poems like “Conversion,” “holy, holy,” and “Memories of Revival,” they feel more grounded in a palpable experiential knowledge. By the time we get to Pastoral and Tether, it feels more ritualistic and symbolic; well, when we get to Riding Westward, it feels like it’s using the spirit through a new experience. In that book, I’m thinking about some poems that may not look spiritual on the surface: “A Summer,” Affliction,” “The Cure,” and, maybe moreso, “Swear to God.” Is it fair to say that there’s a correlation between your trajectory through manhood—and, more fully, as a gay man—to your spirituality? I know from my own experience, the journey through manhood has brought on a better defined sense of spirit in me. One can define this as spirituality, maturity or my being better in tune with my vulnerabilities. I think this is what men mean when they say they know their limitations. I think it’s a way not to deal with spirituality. So, I’m curious to know if any of these rumblings have been a part of your journey.

Phillips: Maybe the hardest question I’ve ever been asked! I don’t know what the word would be—I agree with you that spirituality is probably not it, or at least not for me. When I look at the trajectory you’ve pointed to in the poems, I start to think that the movement is from a false sense of security to a sometimes terrifying suspicion that there are no limitations (except mortality, of course). I think the tendency, in times of disorientation, is to turn to something that might orient and provide structure—ritual, for example. But when the ritualized can turn out to also be an area for disorientation and vulnerability, the choice seems to be that we can be broken by our situation, or we can abandon ourselves to it, or it can make us all the more transgressive…I grew up believing, naively, that there were fixed rules to everything, that it was possible to chart a course for oneself and everything would work out as planned. But nothing I have ended up doing has been what I expected. I didn’t ‘expect’ to turn out to be a gay man—how could I, when I had never heard of anything like homosexuality as an actual part of identity until late in college? I knew, by high school, that for a man to feel sexual about another man was considered perverted—the idea, then, was not to feel sexual about another man, or not to speak of it, and certainly not to act on it. When I first started writing (in response to my grappling with confusion about sexuality), and started reading contemporary poetry, I despaired because my poems didn’t seem to sound like other poems I was encountering. I was lucky in finding a reader and teacher, Alan Dugan, who convinced me to forget about rules, about how things were ‘supposed to’ sound in a poem, and what a poem was ‘supposed to’ be … Have I strayed from your question? I hope not … I’ll end by saying that my concern is not with knowing my limitations, by with seeing the idea of limitation as a catalyst for challenging those limitations—and that can be dangerous, I know. There are reasons why the idea of limitations exists. Limits—and understanding them—can save your life. But I don’t know that we can keep growing, as artists, as human beings, if we don’t continue to take risks, and refuse limitation.

[The following poem seems to me to be IMPOSSIBLE to format on the web. Please buy Shadowgraph One to see it in print, or Carl Phillips’ book, Speak Low, to see the real formatting. Meanwhile, I’m working on it …]

Rubicon

Carl Phillips

Like that feeling inside the mouth as it makes of obscenity

a new endearment. Like a rumor-monger without sign among

the deaf,

the speechless. Having been able, once, not only

to pick out the one crow in a cast of ravens, but to parse darker,

even more difficult distinctions: weakness and martyrdom;

waves, and the receding fact of them as they again

come back;

bewilderment and, as if inescapable, that streak of cruelty to

which by daybreak we confess ourselves resigned, by noon

accustomed, by night

devoted—feverish: now a tinderbox

in flames, now the flames themselves, that moment in intimacy

when sorrow, fear, and anger cross in unison the same face,

what at first can seem almost

a form of pleasure, a mistake as

easy, presumably, as it’s forgivable. I suspect forgetting will be

a very different thing: more rough, less blue, more lit, and patternless.