C.D. Wright has published over a dozen books of poetry and prose. Her most recent, One With Others: a little book of her days, won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Lenore Marshall Award. Other awards include a MacArthur Fellowship, Lannan Award and Robert Creeley Award. She is on the faculty at Brown University in Providence.

Shadowgraph: Your use of documentary elements is interesting because you fuse the personal with the historical, mix them up, allow them to inform and guide you but not really direct the trajectory …. how does the research you do end up affecting not only your work but your life and how you live it?

C.D. Wright: I like to read and I like to pursue a subject—with books, music, films, personal contact. It is part of my self-education. Never mind that I don’t retain much of the ground I cover—I have a detailed but distilled, shaped but open-ended record of what I learned. The concerns of the writing are not altogether distinct from the life I live.

Shadowgraph: Many of your books are explorations that follow a historical arc, and character studies of a time and place. The South, as a place, both real and mythical, is a location for a lot of your work. From Cooling Time: “I poetry.” “I also arkansas.” We all live in a place that to some degree defines and determines much of what we experience. But some people also take that experience and place as part of their identity. Would you care to tell us a little about your “South”? You as the South?

C.D. Wright: I’ve been living in southern New England for over thirty years. I am currently spending more and more time on the West Coast. My formative years and beyond were mostly spent in Arkansas and Tennessee. You drag it all around with you. My most current manuscript concerns beech trees, mostly Fagus Sylvatica and its varieties. These specimen trees are all over Rhode Island. I think my subjects will vary geographically more than they have in the past. I collaborated for a number of years with a photographer from Arkansas based in New Orleans. I also had some nagging old subjects to address that took me back. I’m ready to look outward. I would like to continue to have a relationship with Mexico and if I do, I expect to take it in with eyes wide open.

Shadowgraph: I realize that “interviews” are rational quests, and that you probably say most of what you’d like to say, the way you’d like to say it, in your books and poems. But I’d love for you to send us a poem, an image, your notes, various things that would add to our understanding of your creative process. I’d love to have an interview with you that is also like an “investigation” or “vigil”—words stolen from your books.

C. D. Wright: I include a few photographs of beech trees. I wrote a manuscript on beech trees and took scores of amateur photos with my phone as mnemonics. These are my favorite European beech trees: a weeping beech, tortuosa, copper beech, and fern leaf. All but the tortuosa are in Rhode Island, and it is in nearby Cambridge’s (Harvard’s) Arnold Arboretum.

Weeping Beech

Tortuosa

Copper Beech

Fern Leaf

Shadowgraph: I’m interested in your experience as a woman in the world of literature. Did you encounter difficulties in your career as a poet?

D. Wright: I don’t think I viewed any obstacles encountered in my writing life as anything more than challenges to writing period and to being period. The feminist movement was part of the experience of my twenties as was the civil rights movement and the peace movement during the Vietnam War. Those were periods of growth, collective strengthening. Language Poetry constituted a startling encounter for someone who had not spent her life in an urban environment. My education was spottier than many of the intellectuals I would meet in San Francisco and New York and Providence. I didn’t feel unequal. These people did not know the deep, clear springs I had to draw on—my rather different reading background, the examples of my father, my friend Peggy Vittitow, and a few phenomenal teachers such as the comparative literature scholar Ben Kimpel. I did feel challenged, but not lastingly intimidated out of my own outsider heritage.

Shadowgraph: In Cooling Time you write, “It is the function of poetry to locate these zones inside us that would be free, and declare them so.” In the context, it seems that you are talking about poetic form, but I’m curious, do you hope to bring a kind of freedom to your readers? Can you elaborate on your ideas of what freedom (personal, poetic, political, etc.) is?

C.D. Wright: Freedom is oddly confined in my mind. It is tightly connected to truth-telling. If you tell a hideous lie, you are hideously confined; a minor lie, comparably so. Freedom has more to do with commitment to what you believe in than “anything goes.” I wouldn’t damn “anything goes,” except to people who pretend otherwise. It’s so simple and so difficult to live by your words, and the price of not doing this is bound to be cruel.

Shadowgraph: One of the themes of Deepstep Come Shining (and other works) is seeing: how to see, who sees who, what it means to see something. One stance as a writer is to witness. Your work is never fixed in a position of pure witnessing, but also includes participation, however indirect. There is an inside/outside experience of the experience. To what extent do you try to be objective? To what extent are you aware when writing of representing both your personal take and the other realities that you are writing about?

D. Wright: Objectivity, even in science, is not on solid ground. The effort for me is not to wallow in my biases. Vocally, I can be quite knee-jerk. Tap that spot and up flies my leg. Even trying to avoid that in writing requires repeated scrutiny. It might include a mantra-like phrase such as—things are not altogether this way or that way. Still I dislike the grey areas and I try to get on the most honest side of that mushy divide as I possibly, humanly can. When my opinions are foregrounds, I try to enter them as precisely and conspicuously as they are. I really want to understand a few things during my split moment of time here.

Shadowgraph: A typical section of One Big Self is like this:

My friend here no longer sleeps in her own bed in

her own house by her own self

The Heisenberg principle applies

you change what you observe

EVERYTHING IS PERSONAL

Did you ever do anything illegal

Maybe Maybe not Depends on your definition of legal

Who you going to believe me or my lying eyes

This stance requires agility on your part—shifting from voice to voice—from philosophy to science to personal voice to outright humor, and I’m wondering if this associative process comes to you naturally as you write, or do you find later, in revising, that you weave in other materials to create the associations?

C.D. Wright: I don’t know how to explain my spidery maneuvers except to say that I try things, and thinking associatively is perhaps the part that comes most naturally, though even that has to do with a developmental process in the writing.

Shadowgraph: I love your answer about the theme of “freedom.” It’s interesting in itself, but your answer is also connected to another of your frequent themes: the “truth.” If the “truth” has components of subjectivity to it, could you elaborate on how you understand “truth” and how that has been a part of your work?

C.D. Wright: I asked a philosopher about his writing and he said he had written a book about truth, and I replied, I was interested in truth. I bought the book and e-mailed him that I had, and he said, “Oh, C.D., maybe the intro would be of interest to you.” And he was right. The rest was impenetrable. He had also told me that one of the most frustrating things about philosophy was that you could work on a problem for years stretching into decades and be point blank wrong. I may not have more to say about the “truth.” I can be very black and white about it in every day life. I don’t like being lied to. I don’t like lying. But that does not mean I hold the golden key to truth. It remains the truth as I understand it in these circumstances. But I am always trying very hard to understand the implications of any environment in which I find myself.

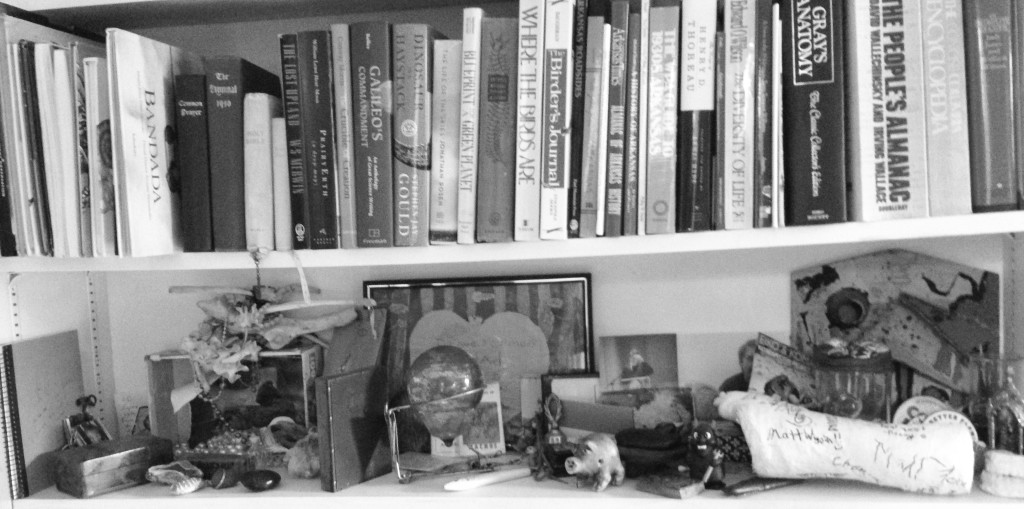

This photograph pertains to something I do with almost every project, which is to create a project of what I consider to be resonant associations. This particular shelf is a jumble and doesn’t represent the discreteness of a single project because I’ve struck that set already.