Chemo/Chromo-Ryoichi at HOA (Hematology/Oncology Associates), Abq, NM 2014-2015

Patrick Ryoichi Nagatani’s survey show and book, Desire for Magic – Patrick Nagatani 1978-2008, premiered at the University of New Mexico, traveled to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, and was exhibited at the Clay Center for the Arts and Sciences of West Virginia. He has received numerous awards, including two National Endowment for the Arts grants; The Aaron Siskind Foundation Individual Photographer’s Fellowship; The Kraszna-Krausz Award for his book Nuclear Enchantment; the Leopold Godowsky Jr. Color Photography Award; the Eliot Porter Fellowship in New Mexico; and the California Distinguished Artist Award from the National Art Education Association. Currently he is writing and editing a collaborative novel called The Race. His official website is: http://www.patricknagatani.com.

Shadowgraph: One of the predominate themes in both your writing and image-making is the promise that magic holds. What are your current ideas about magic?

Patrick Nagatani: Ah. A perceptive question … and it has shifted. Magic used to be for me the acceptance of created magic. In other words, there was always a trick, and I loved seeing the way the tricks occurred, and how the viewer was made to think about how the trick was created. Today, I don’t care about the tricks. I just go with what I see and feel from the place of magic. I’m thinking about magic for myself these days in terms of something that is out of my control, something that is supernatural and beautiful and thought-provoking. I no longer think about where it came from, the reasons for its existence, or how it was created.

The shift in my work from the early days of nuclear issues, or documenting the location of Japanese relocation camps, or the ideas of astronomy, archeology, and alien landings … these ideas are still there, and I still do that research, but in my current work I’m looking for a different conceptual basis, more about process, and during the process I’m embracing the time-lapse, the meditation, the no-thought place while actually doing the work. So lately, I’m attracted to work in which I sense that the artist had that place of a magical no-zone.

Tape-estry: Uncertainity

Shadowgraph: For a while, the Tape-estries were your place of no-thought. Do you have a new place of no-thought?

Nagatani: They were definitely the transition from the work I’d done in the past. The statement for the Tape-estry pieces (we’re always required to write statements) talks about time lapses and the meditative quality of the process. It is also about not the finished product, but the work that goes into making the work.

Shadowgraph: So, you’ve been interested in chromotherapy for a long time. Are you exploring chromotherapy in a different way with your current health condition?

Nagatani: Oh definitely. I’ve worked with a curator at SCA, which is a gallery warehouse here in Albuquerque. A group of artists here make art as a healing process. We think in those terms. The art isn’t separate from the condition. It is a way to either express oneself or what one is going through, or to actually hold a line to a place that is about constructive, positive thoughts. The one image I made in 2014 was of myself getting chemotherapy. People have said, “Wow, you look great in that picture, Patrick.” And I say, “THAT guy looks great.” And he’s surrounded by three beautiful oncology nurses and one of them is applying chromotherapy. It’s a fantasy place. I’ve been wanting to make these things ironic, funny, and dark at the same time. So here’s a dude, getting chemo, and the chemicals are going into a port in his chest, and he’s just sitting there, surrounded by beautiful women fanning him. So someone might say, Gee, I want to do that too. Like, right. But that’s the impetus for my picture making today. My current work, a novel, pursues a similar direction. This novel, in fact, has fifteen different characters. Many of their stories take place as they fly their British Spitfire air float planes in a race from Tokyo to San Francisco. There is no real chronological time: it is in the future, the past, and now. I’m really only writing five of the fifteen stories. I’ve got ten writers who have written for the other pilots.

The Race

The Race

Shadowgraph: The humor you’re implying has been employed throughout your photographic career to present the paradox of destruction and creation. What do you think about the irony of having spent so much of your career thinking about nuclear issues and technology, and now you are immersed in nuclear technology in a very personal way?

Nagatani: It’s very interesting. I am a researcher and observer of technology. I compare digital CT scans today which are computer generated, to the images coming out of Kitt Peak National Observatory. The director there took us to see eighteen telescopes. We saw the old photographic lenticular photochemical method of shooting—very work-intensive—to get three images a day was phenomenal. Then the director showed us the current astronomical telescopes sending in computer information, all instantly translated to so many monitors.

It was similar to both my process in art and ultimately the bigger picture of my life: Yeah, I’m an observer of technology and nuclear issues. And I’m still the observer as I watch the black tidal wave of Fukushima. I found out that I had relatives near the Fukushima nuclear plant and they refused to move. They just want the government to clean up their farm. Of course, nobody knows how, but they’re attempting to do that. I want to talk to my relatives; I’ve never met them before. I’d like to talk to them about how decisions affect evertyhing: how firmly we stand or how we shift in our decisions. I used to observe technology, now, I am its subject: twenty-three days straight of getting radiation put into me for healing. This is a whole different aspect of maintaining life as far as how the medical profession uses nuclear technology today, compared to taking life using similar technology to create nuclear weapons or uranium tipped ammunition.

Shadowgraph: One of the essays in your book, Desire for Magic, discussed the artist-as-witness, and the witness-as-accomplice. So many of your characters, with nuclear bombs blasting outside their windows, are unaware of what is happening around them. This state of unawareness is both hilarious and absurd but points to the layers of conflicting awareness—the characters in the photos are oblivious, but the viewers of the images know the historical context. Do you imagine that the viewers become a witness to their own lack of awareness?

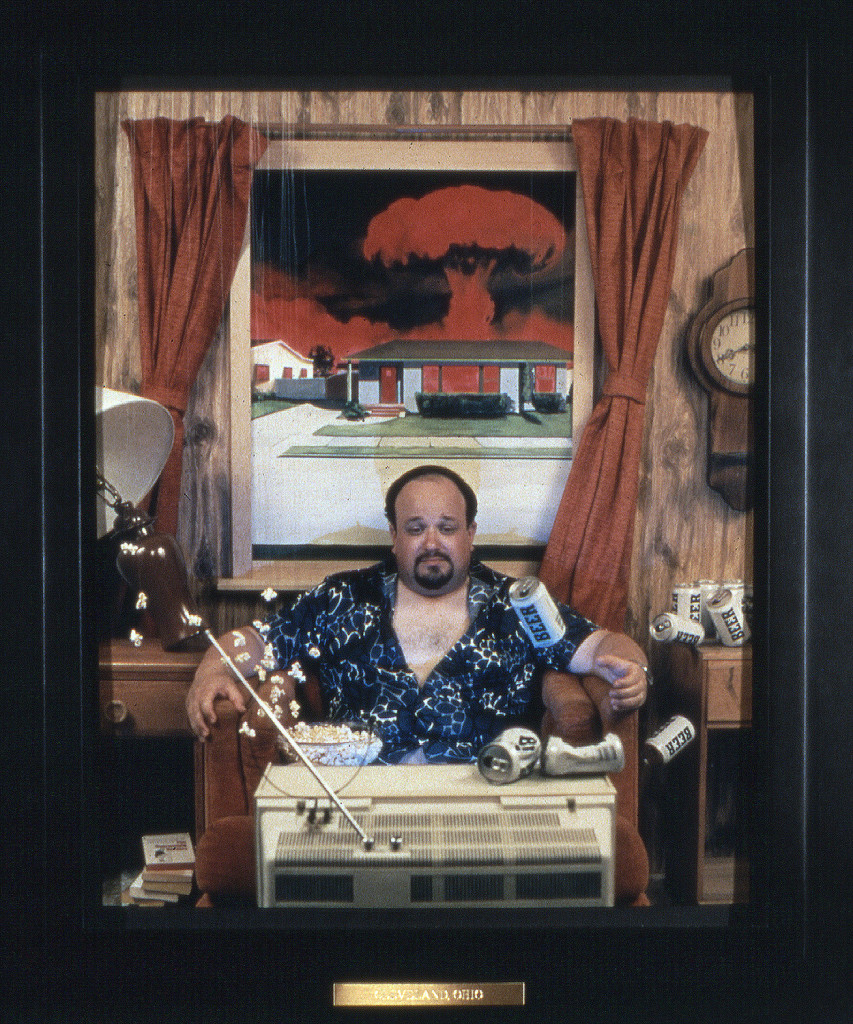

Radioactive Inactives, Cleveland, Ohio, 1987-1988, Chromogenic print (Kodak Ektacolor Plus), 20×16

Nagatani: The culture back in the 80’s, when I was making the original Polaroids, was that people were are all carrying on with their business like it won’t touch me.

World wars have not touched American soil. Europeans, at least the ones who lived through these wars, have experienced, in a more direct way, the life and death of what war is about. Americans, on the other hand, have a lot of distractions and denial and in some ways no education about war. So a lot of that work [the Nagatani-Tracey Collaboration] dealt with that kind of cultural context. The images are also oriented around the moment of a nuclear blast, which, like the one in the New York City subway, is theater, fantasy. Both Andrée [Tracey] and I know we are a part of that same milieu. As I’m going to a football game or going to a movie, or to some fine dining place, I’m really in denial about what’s happening to the rest of the world. And then my thinking is, Well, what can I do about it? Well, I’m going to enjoy my meal, and go out there and be aware of things but there’s not much I can do about it. So the point in making the work, was making images about this paradox and making people think about that—but we weren’t motivated as activists as much as I’m articulating right now. We wanted to make funny, dark, ironic images around the idea of the nuclear blast because our objective was to use red, the red of the Polaroid material, and paint our props red in a conceptual, photographic image-making way to show the construction. We showed the monofilament line, we showed the façade. In a kind of precursor to Photoshop, we wanted to show how things were made rather than create the illusion of reality. Though that might be only 25% of what occurs to a viewer … they know they are looking at a theatrical set, and then they become fascinated and wonder, Wow, did these guys string up 200 pieces of a light bulb that is exploding? And the answer is, Yes! So it was about both a kind of obsessiveness and also about working with certain technologies that weren’t available to everyone. We were using a big 20 X 24 camera that made instant pictures right there and we became directors and stage managers and prop designers—everything … and every once in a while we got to push the cable release of the camera and I got to act like I was a photographer. We even got help in the lighting of the sets. So making the sets and creating that visual moment was the most important aspect for us as artists, and that continued in the future for me. It was always interesting for me to analyze where the most magic, the most fun was. And it was often in creating the setup rather than deciding on the photographic materials or process and making the pictures myself by hand either with tubes or a color processor. The magic was in making the set, and fantasizing myself into the set, which I often did. So I’ve tried to carry on that kind of thinking. And again, it might allude to me wanting to be the subject of the fantasies I create. That seems to me to be okay these days. Because I don’t want to be in the reality of where I am.

Shadowgraph: When you talk about your no-thought place, would you call that a heightened awareness or a place without history?

34th & Chambers, 1985, Polaroid Polacolor ER 20×24 Land Prints Diffusion transfer prints), 24 x 60

Nagatani: If anything, it’s heightened awareness—where I am aware of the moment, and what I am seeing and feeling. My parents both passed away at home in a beautiful way with their families near. My mother suffered from Alzheimer’s. She thought so vividly about the past, but she couldn’t even relate to three minutes ago. Her thinking and inability to remember her own history made me consider a lot of things, and that brought me, probably, to the novel and how these characters are thinking about dealing with the present. They might be recognizing issues from their past while they are flying in the air in a quiet space removed from the issues of the ground. Some of them face a life or death situation that enhances each moment, which is a great deal of what the novel is about.

Shadowgraph: One of the questions that comes up in your work, which maybe both you and the viewer asks, is, “What is real?” Would an actual light in a particular color put on your body be more real or less real than thinking about a color moving through your body, perhaps as meditation?

Nagatani: Ah yes, I think they are equal. I might harken this idea of realism to the process that I’ve used my whole life—from the beginning, in the 70’s, my idea of photography was that of façade and the creation of effect. But, really, all pictures just represent some specific point in time. Within that, how much do I want an image to portray “the truth” or “facts” and how much am I willing for the work to be deconstructed or to show the façade? I think about the portrait photography of E.J. Bellocq, his images of prostitutes in Storyville at the turn of the century. His glass plates would show the piece of cloth strung up on a clothesline as a backdrop to eliminate what was behind the woman. And the woman … not naked, as her profession demanded, but maybe in a slip or a dress … perhaps she’s off work, but there is this hint of the occupation she has, revealed in that odd moment. I’ve always thought about the images where you see some aspect of façade, which is okay, because then one thinks about the perception of reality, and then maybe that thought evolves into the displacement of disbelief.

Shadowgraph: Do you know how long you have to continue in your treatment?

Nagatani: I don’t know, since it is Stage 4 Metastatic, for the rest of my life. But I’m learning to accept it. There are certain aspects where I feel I’m losing male thinking and moving into a more female realm. I used to think, things are real or phony—they have to be one or the other, they can’t be in between—but that’s not where I am these days. I cry a lot. I say something to myself about my parents in a moment and I’ll start to cry. I see something beautiful and I cry. And I try to use that intuitive compassion even when I’m out there at the Indian Casinos and gambling and it works. The strong intuitive process has greatly increased. And the ability to find those magical moments and magical places has increased.

Shadowgraph: I’ve experienced that whenever I have to deal with a lot of physical pain, I get closer to my emotions.

Nagatani: Yeah. I’ve become more in touch with myself, my thinking, my past, and my compassion. And I think, when I reach that point where whatever I feel is relative, there are other people who are suffering just as much, or more, but everyone counts. I’m not the only one dealing with things in the world. I’ve removed myself from my Self. I look at the cosmos, and think about the insignificance of singular beings. Really taking the opposite stance. It can broaden one’s perspective and meaning. And then looking at things much smaller than the cosmos, microscopic. And then in the final analysis, just embrace the moment, the things around you, the leaves, the trees, the wind, the person you’re with, what you are doing and those types of things. These are the polarized places I think one gravitates to and embraces, and it’s interesting what is forgotten between the poles. I don’t even want to read the front page of the paper anymore. I play fantasy football and baseball with my son and basically I’m winning in all of these leagues. (laughter)