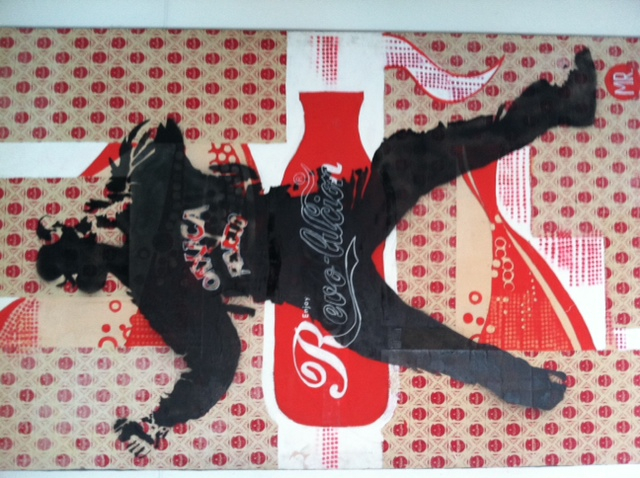

Photo: Curtis Bauer

Curtis Bauer

Dispatch on Disorientation #2:

The Changing Meaning of Who I Am

A month ago the papers were filled with photos of several thousand citizens in Buenos Aires gathered in Plaza Mayo, some holding signs “Justicia” or “Castigo” or “Yo Soy Nisman!” while others stood, faces frowned and fists raised in the direction of the President’s residence. Theirs were portraits of anger, of protest, of solidarity inside uncertainty, questioning whether the government was involved in federal prosecutor Alberto Nisman’s death.

Chance took me to Plaza Mayo that evening. I’d started wandering the streets without a map, trusting the meander as I’ve learned to trust odd encounters like this to give insight into what I should understand about a place, to offer up some knowledge, or some experience to draw from in order to make sense of what is happening there on a day-to- day level; it’s a movement toward orientation. Today I still find I’m thinking about the signs I saw then, how they upset me a little, making me think of the protests in Paris the week before—Je suis Charlie—and those from the previous months and years—I am Darren Wilson, or I am Trayvon Martin—on the streets of the US.

In Argentina I’m no one; I am a foreigner; I am an English speaker until I open my mouth, then I’m asked what part of Spain I’m from. I used to try to hide the Midwest in me, and the U.S., tried to be someone I wasn’t instead of who I was, an act I hope I’ve outgrown. Now I’m mostly disoriented by all the stimulus of these latest events. Proficiency in the language and the ability to study current politics do little to help me understand the nuances of a place like Argentina. Yesterday I scrawled an idea on a napkin—What makes one neutral is ignorance. But maybe it’s knowing everything; maybe reading the newspapers or watching news programs makes one walk down the middle-of-the-road. Most days, after reading Clarín and then La Nación or Página 12, I think I have enough information to know something, to have an opinion about the causes and consequences and confusion in this country, but then I realize I’m completely lost.

Not everyone had signs. Most of the thousands were clapping or banging on something, and others were taking their selfies or recording video of the scene. A few children stood up in their parents’ arms, or were held close by grandparents; in the crowd of young and old several noticeable foreigners like me lingered, as if the plaza were an immense classroom and the crowd were giving us a history lesson, perhaps trying to clap into our heads the rules of civics, the right and reason to protest, perhaps even the difference between what’s acceptable and what’s not in the still present shadow of a dictatorship.

A month has passed and I’m still disoriented in this city and reading the news, getting lost just about every day, just as I’m getting lost in these ideas about politics in a young democracy: is my conclusion that very little has changed? do I know enough to have an opinion? should any of this matter to me, foreigner, nobody, wanderer that I am? Of course. Of course. Today there will be a silent march to commemorate the month of doubt the country and its citizens have tolerated, a march some members of Kirchner’s government are comparing to the makings of a coup. The questions one sees in the papers keep afloat ideas of whether Nisman’s death was murder or suicide; people still wonder if the government was involved, or if it was the Iranians, or maybe the CIA; columnists search for evidence of culpability in the President’s silence, even in the fact that she hasn’t expressed her condolences to Nisman’s family. And yesterday, the day before the massive demonstration against the government’s deeds in the face of this crisis, Clarín dedicated several pages to the story of a waitress who was picked up by government agents the night of Nisman’s death and taken to his apartment to act as a public witness of what was found there, concluding that she seemed to be more careful, more vigilant than the government investigators.

In the midst of the crowd in Plaza Mayo, I was surprised at how the Argentine citizen could be so quick to doubt the government’s clean hands in this action. I’m naive, and I’ve never lived under the fist of a dictator. I take for granted that a national government is going to act honestly and morally. And as I write this I recognize how ignorant I sound, how simple, how innocent, how utterly first-world oriented. How else does one become aware of the world one lives in, become an active citizen in a global community, if not by living in the middle of an aggression and observing how a country comes together to respond, practicing the lesson of questioning what isn’t said, searching out what is withheld? An editorial comes to mind from the paper Página 12 (the left-leaning paper here) which compared Argentina’s disappeared during the dictatorship to the many people killed senselessly around the world today, how no one said I am Nidia Fontanellas or I am Estella Altamirano (two women shot and killed during the 80s, and both pregnant), or all the other countless revolutionaries who became enemies of the state the moment they walked down the street during a police raid, or went to university classes, or read books, or wrote books here. No one says I am the child who died of malnutrition in Salta or I am the field worker dying for Monsanto’s profit or I am the man who lost his whole family in Syrian air raids. And at home? How can I not think of my own country where aggression and violence and dishonesty are perpetrated daily for profit and power, where black men and boys have been, still are, harassed, jailed, beaten within the rule of the law. Why have I done nothing to write about that? My silence, my neutrality.

I am not Charlie. I am not Alberto. I am not Trayvon, and I have not searched for my family and friends under bomb rubble … but that does not mean I do not protest what happened to each of them and countless others, that I do not criticize and condemn those aggressors. Only as myself can I do anything about it. Only as an individual writing and acting under my own name and words, for a common cause, against wrongs, violence, and injustice will I accomplish some kind of change. I don’t want to carry the regret of silence. Even thinking whether or not I send this to friends back home, whether they will disagree, realize I’m simple, fills me with anxiety, though I realize this is a conversation a writer needs to have—a citizen needs to have. Before I walk out to join today’s march, finally, I send these words to you.

Photo: Curtis Bauer