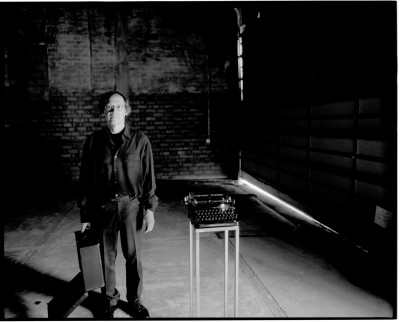

Arthur Sze is the author of nine books of poetry, including Compass Rose (forthcoming from Copper Canyon Press in 2014), Ginko Light (Copper Canyon Press 2009), Quipu (Copper Canyon Press, 2005), The Redshifting Web: Poems 1970-1998 (Copper Canyon, 1998), and The Silk Dragon: Translations from the Chinese (Copper Canyon Press). He was the first poet laureate of Santa Fe and is also a professor emeritus at the Institute of American Indian Arts.

Interview by Miriam Sagan.

Sagan: Contemporary poetry runs the spectrum in terms of the overt subject matter from confessional to something like Language School—essentially from where subject dominates to where style dominates. Do you consider your work to be based partially on abstraction or is it rather a very dense way of approaching experience in language? What is your opinion about the issue of obscurity in poetry?

Sze: I like poems that are rich in layering: if a poem has multiple meanings, then the experience of the poem grows and deepens with repeated readings. Wallace Stevens once said, “Poetry must resist the intelligence almost successfully.” I believe that a good poem communicates before it’s fully understood, that the intelligence cannot understand the poem right away, that it takes time; but the initial experience is more of a physical and mysterious one, rather than a cerebral one.

My poems, then, are not based on abstraction, though I am interested in harnessing ideas. The great Japanese potter, Rosanjin, once remarked, “Without extraordinary ideas, there can not be extraordinary results.” I am often interested in having an idea that works as a through-line: for instance, in Quipu, the recording system of knotted cords serves as a metaphor for how language can be spun, dyed, and knotted, but it also serves as a metaphor for lyric composition: “the mind ties knots, and I / follow a series of short strings to a loose end.” I can say this in hindsight, but I could not have articulated it during the process of creation.

I value clarity rather than obscurity—and I am certainly opposed to willful obscurity–but we need poems that can articulate complex visions and experiences of the world. In doing so, poetry may make demands on a reader, but they are worthy ones. I believe poetry is more crucial now than ever before, because we are more challenged than ever before.

Sagan: I assume most readers on approaching your work wouldn’t immediately identify it as autobiographical. Yet it is full of images—and themes—that seem based on daily domestic life (albeit mixed in with other concerns, such as science, time, etc.) Can you explain how narrative you want the work to be?

Sze: I’m interested in simultaneities, and my experience of the world is more like an ancient game of go than a traditional, linear narrative. I suppose I’m interested in a narrative of consciousness, where imaginative and emotional leaps can happen and happen in ways that are surprising and revelatory. In this way, I often use images and events out of daily domestic life (I like that grounding), but I like to think of these events as vehicles to reveal and revel in a larger, greater sense of the world.

Sagan: Although influence can be both direct or more ephemeral, I am curious about the influence of what you translate on what you write. I have always been intrigued by your use of the line in your poetry–the lines in your work seem unusually autonomous but connected somehow to the whole poem. Does this come in some way from Chinese poetry? Do other techniques?

Sze: The influence of translating Chinese poetry on my own poetry is more oblique than direct. When I starting translating Li Po, Tu Fu, and Wang Wei in 1971, I was in search of my own voice. I think that Chinese poetry made me recognize the power and even primacy of sharp visual images and that it had a precision and clarity that I wanted to emulate. In 1983, when I translated Wen I-to, I was searching for how to extend a poem beyond 20-30 lines. Wen I-to, as in “Dead Water,” takes many classic T’ang dynasty images and subverts them, or juxtaposes the harsh realities of twentienth-century China against the pure lyric. He is also able to extend and extend a poem, as in “Miracle,” with great emotional and imaginative power. I didn’t copy him, but, by translating Wen I-to, I was able to discover how to greatly deepen and expand the range of a poem.

When you ask about my use of the line in poetry–that it’s unusually autonomous but connected somehow to the whole poem, I would say that this effect comes from Japanese as well as Chinese poetry. I visited Ryoanji Temple in Kyoto in 1990, and it was a pivotal experience. In that space of raked gravel, there are fifteen stones, set in clusters; and they are situated in such positions that a viewer can never see all fifteen at the same time. The stones are submerged at different depths; yet they are connected below surface. When I came back to New Mexico, I read some translations of Japanese haiku by Hiroaki Sato. He mentions that, unlike most translators of Japanese haiku, he prefers to render the entire haiku in one line. I know many translators of Japanese haiku may object to this practice, but I liked the sense of a clear and intense haiku happening in a one-line flash. I began to experiment with opening up the space of the page to incorporate more silence (as in the raked gravel) but wanted to keep sharp, intense images that had an emotional weight (as in the stones).

Sagan: You don’t write prose or criticism, seem dedicated to the pure pursuit of poetry, so translation is your only other form of writing. What is the genesis of the interest, how does it work for you–is it a different muscle than writing poetry?

Sze: It’s true that I write very little prose or criticism. I’ve wanted to put all of my energy into writing poems, and the translation work is a kind of ground work. I like to write out the poems that I translate character by character, stroke by stroke. It enables me to physically experience the inner motion of a poem. And as the poem unfolds, I am given the opportunity to consider why this character, and not another, is located where it is. In many ways, translation exercises the same muscles that writing a poem does, but the muscle groups are easier to separate and focus on in a translation. Hopefully, when you turn to write a poem, you discover that your muscles are well-toned and much stronger.

Sagan: I’ve heard you say that juxtaposition is a central technique in your work, placing things side by side. But it seems to have a somewhat different meaning to you than metaphor. Can you elaborate?

Sze: When people raise the issue of juxtaposition in my poetry, they often think of such western antecedents as surrealism, cubism, collage etc. That’s certainly a factor, but I would mention that the Chinese language is built around juxtaposition as a form of metaphor. The character “bright,” for instance is composed of “sun” juxtaposed to “moon.” The character “sorrow,” for instance, has “autumn” (which is composed of “plant tip” and “fire”) above, and “heart” below. One can thus read sorrow = autumn in the heart. Oftentimes the equal sign of the metaphor relation is removed, so that the two energies are brought into a field of interaction. The metaphor is indicated obliquely.